“Palimpsest”

After flocculation and thalweg, palimpsest is my third favourite geographical term. That is both for the poetry of the word itself and, more importantly because it is a single term that encapsulates a powerful and important idea in understanding places.

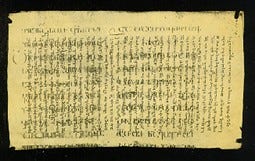

In the early Middle Ages people wrote on parchments made from animal skins which were expensive and not easy to obtain. If you found yourself with some written work on a parchment that you no longer needed you might scrape or wash off the previous writing and reuse it (‘palimpsest’ comes from the Latin for ‘scrape again’). However, over time the faint traces of the writing underneath might re-emerge. These documents – or palimpsests – can be of great value to medieval scholars.

Places are palimpsests too. Jon Anderson wrote that places are ‘ongoing compositions of traces’. Just as scholars in the early Middle Ages kept adding layers of text to their parchment so we add layers of meaning to our places. Just as they didn’t always successfully remove previous traces so do we leave traces in places as we change and develop them. And, just as modern scholars can peer carefully at a palimpsest to decipher previous meanings so can we look carefully at modern places to find traces of their previous meanings.

The Edict of Nantes had protected the rights of French Huguenots to practice their religion. When it was revoked in 1685 many fled France, often finding their way to East London and Spitalfields. They came to London poor with little beyond their skills in silk and textile weaving. This led to the area developing an agglomeration of textile industries.

This migration over 400 years ago is still visible as a faint trace in the landscape of Spitalfields. Before the advent of electricity the buildings needed to be designed with large, wide windows to maximise the light available to the weavers conduct their intricate work. While few of the original such windows remain so many hundreds of years later, the design choices live on the style of many more recent buildings.

Other traces of the area’s textile industry heritage remain. To avoid the time and labour challenge of lugging materials up and finished products down several flights of stairs the textile factories and warehouses installed cranes on the exterior walls of their buildings. Industrial change has led to the textile industries moving out of central London, and through global shift towards developing countries in Asia. The parchment has been wiped clean and those factories and warehouses have been converted into apartments and offices. However, as the medieval scribes found they could never fully clear the parchment so those cranes remain on the sides of the repurposed buildings to offer a hint at the place’s former function.